In this post I’m going to argue that bringing pre-existing off-the-shelf models and frameworks to my client work is the biggest mistake I’ve made in the past two years.

A framework as I’m going to refer to it in this post is essentially a useful abstraction. A tool for thinking about a situation that allows teams to use a shared mental model and a shared vocabulary.

In my post ways of seeing - I explored the idea of deeply understanding a client’s organization and culture to better understand how they see the world. I ended with the idea that “teaching a client new ways of seeing is the pinnacle of consulting”.

But how exactly do you teach clients how to see?

The answer is frameworks. Douglas Hofstadter claims analogy is the core of cognition1 and I’d stretch that to say frameworks are the core of cognition for organizations.

A good framework is a tool for thinking. A shared mental model of a situation is powerful and deeply transformative, especially at the management layer where they spend most of their time in abstractions.

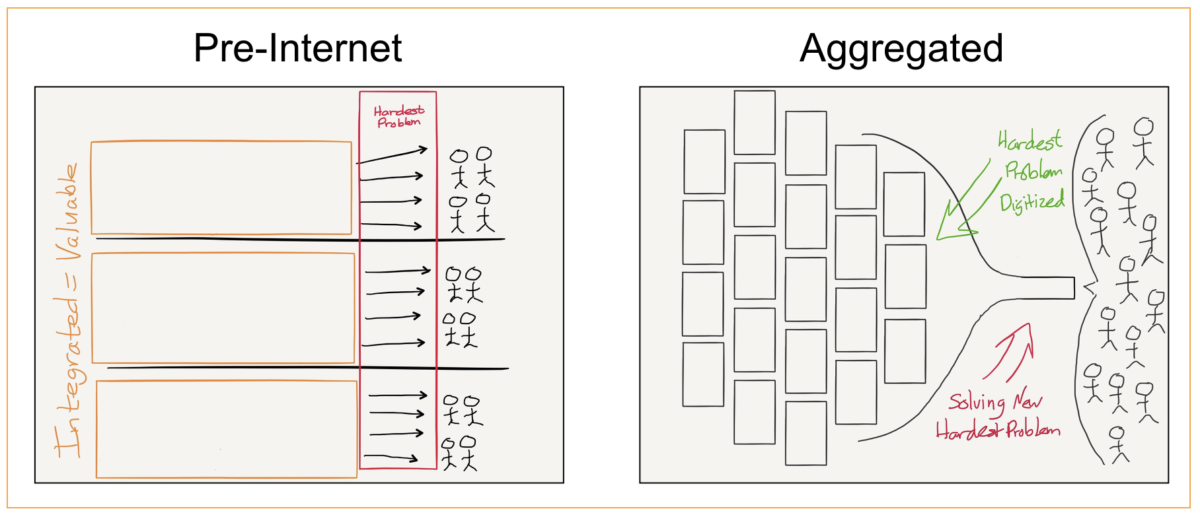

Something like aggregation theory from Ben Thompson is a good example of a pre-existing framework that you might be tempted to reference in client work.

But, to be successful a good framework needs to be simple, true and co-created:

Off the shelf frameworks have a hard time meeting any of these three goals, and in particular can be dangerous when applied to the wrong problem. And it’s only recently that I really began to understand why existing generic frameworks like “jobs to be done” don’t meet my needs.

A strong framework is a powerful tool.

And for extra impact get good at naming them and embedding them in processes to achieve the outcomes they want.

I’m going to try and walk through what this all means, show four case studies from my consulting work and end on some ways you can practice making frameworks.

First, let’s lay the groundwork and set some definitions - in particular let’s try and differentiate between the concept of a “model” and a “framework”.

The dictionary defines a framework as:

a system of rules, ideas, or beliefs that is used to plan or decide something

This is close to what we need - but doesn’t quite capture the notion of abstraction that I think is key for our uses. Let’s re-state as:

A framework is a system of rules, ideas, beliefs or interactions that abstract a situation and can be used to make decisions.

Frameworks are usually scale invariant. I.e. they abstract a system to its core relations, categories and interactions. Then, we can think of a model as a framework that allows for calculation with inputs and outputs:

A model is an analytical framework - i.e. one that embeds an algorithm or set of calculations such that inputs and outputs can be adjusted to interrogate the system.

I realize this is slightly hard to parse and in fact there are so many different uses for the words framework and model. In particular - I think of a “mental model” as actually most of the time being a framework2.

Mostly for this post I’m just going to use the word “framework” everywhere - it’s loose but lets us talk about them all together. They’re all tools for thinking. They’re all in the consultant’s toolkit.

Frameworks are powerful. They help us make sense of situations3:

But frameworks are more than mere representations. As Dubberley suggested, we use frameworks to make sense of and think through the world. A framework can help us break down the constituent elements in a phenomenon – or group of phenomena - which then makes it easier to think about their inter-relationships.

And, they help us communicate more easily about those situations:

Yet beyond being (cognitive) labour saving devices frameworks have another obvious virtue. They provide a shared intellectual scaffolding: a common ground upon which people can interact and engage. In that sense frameworks have communicative virtuosity - they are good to talk with. They allow ideas to be shared.

Both quotes from this excellent short read: Models of enchantment and the enchantment of models from Simon Roberts.

The essence of consulting is navigating unfamiliar organizations to both make sense of existing beliefs, systems and processes while simultaneously helping the organization develop new beliefs, systems and processes. This dual process of sensing and changing is a delicate one.

Unless you’re operating with a team of 4 analytical consultants (like a Bain or McKinsey might) there’s basically no way you can perform a “from first principles” analysis of the client’s organization4. So you’re going to need some shortcuts.

Frameworks provide the shortcut to making sense of an organization and for proposing and socializing new ideas.

But as is always the case with shortcuts, you need to choose your path wisely. Things that look like shortcuts can get you lost…

The biggest mistake I’ve made is bringing pre-existing frameworks with me to a client gig. Pre-existing frameworks are problematic for two reasons:

Pre-existing frameworks are often complex tools. They’re designed to handle many different situations and organizations within a “master” framework so necessarily have to handle many edge cases and environments. They’re complex by design.

But this complexity often means they get used incorrectly.

Let’s take one I see a lot - the “jobs to be done” framework. I hear this referenced on almost every client project I work on in some context. But typically it’s the wrong framework because we’re not analyzing a complete jobs to be done analysis but instead we’re analyzing a specific user need or a functional UX. Yes you could use the JTBD framework here but it’s heavy handed.

Secondly - it’s overly complex. The JTBD framework is nuanced, layered and comes with tons of theory5.

And, by the way, if you’re using an off-the-shelf framework like JTBD then you’re missing the chance to name your own framework. This dramatically reduces the influence you can have within an organization.

So if jobs-to-be-done is too complex, what’s a good simple framework?

I’d propose that for most indie consultants and strategic independents the right complexity is a single idea or concept. Create the most reduced, simple, brain-dead framework that you can find and stick to it.

Jan Chipchase outlines this tension nicely (bolding mine):

“A framework is a way of organising information that supports comprehension and recall. A well-designed framework can communicate both simple and complex ideas without overwhelming the reader. While there are many widely used frameworks that have stood the test of time, every project has unique raw materials that can lead to something new.

A framework, even one that appears at first glance to be mundane, has the potential to reveal the world in a new light.

It takes time to tease out the optimal framework, from the first inkling of an idea run by the team to stress-testing the model to see it if stands up to new data. Novices tend to become enamoured by high-concept/low-data frameworks that take an additional cognitive effort to process and are light on insight.”6

Simple frameworks are easier to communicate, travel faster inside an organization and have fewer barriers to adoption. But what Jan highlights here is that novices become enamoured with high-concept/low-data frameworks - or frameworks that tease the wrong insight.

High concept frameworks are almost by definition worthless - a framework is an abstraction designed for simplifying and socializing an idea and if it’s hard to grok then it doesn’t help people think or help it spread.

Frameworks that tease the wrong insight are what I call “un-true” frameworks and they’re another story…

Un-true frameworks are things that sound nice but simply aren’t saying the right thing7. This is partly why off-the-shelf frameworks are dangerous, because they likely don’t say the thing that the organization needs.

True frameworks are those that are grounded in a very real, practical and necessary insight about the organization, their users or the situation at hand.

This idea of a “true framework” is something that I picked up at a recent sensemaking for impact masterclass from Jan Chipchase of Studio D fame.

Jan walked through his process of turning raw ethnographic interviews into insights and frameworks in a way that generates a throughline from raw research to final deliverable. It looks something like this:

He showed a wall covered in insights gathered from field research - these interviews had generated a ton of little snippets of ideas - these could be insights, quotes or other nuggets. Where every single insight is tagged to the original specific interview that generated it so there’s a throughline from raw interviews to final presentation / output.

He then showed a time-lapse of the sense-making process of turning that wall of insights into clusters of themes. These clusters are what I think most people imagine the sense-making process looks like; conduct interviews, extract insights, cluster and present.

But there was a third wall in the time-lapse video - one for frameworks.

The frameworks wall is nothing more than sheets of A4 paper with sharpie doodles, diagrams and ideas on them. The rule is that you start making a simple line sketch or even just a name for a potential framework - one per page. And during the course of the user research process you refine the frameworks and get rid of the ones that are too complicated or non essential.

Then the crucial step happens last - as the field research nears an end you take stock of the frameworks on the wall and for those that you want to include in the final report you stress-test those frameworks in-field with real users. This ensures that the frameworks are true - they contain real things that map to real users expectations, behaviours and ideas8.

Here’s an example framework from some Studio D work9:

If you look you can imagine the process here from interviews with farmers -> insights -> frameworks like the above.

Why is this important for consultants? Because it shows the power, and the difficulty, of creating true frameworks. Things that have the power to change an organization in the right way and that are tested with real users.

I imagine most indie consultants and strategic independents are looking at this like I’m crazy - who has time for a multi-week ethnographic study in the middle of your consulting work?

But here’s the thing - every time you’re on-site with a client’s organization you’re studying the people, the behaviours, the motivations. You’re asking questions of as many people as you can.

This is all a light-touch ethnographic study of the client’s organization.

I’ve written before about the need to get close enough to a client to understand the “grain” of the organization. You can see how without this close-sensing of the client it’s impossible to pick up on the ethnographies needed to construct these frameworks.

Scanning the kinds of frameworks that Jan Chipchase showed from his work it was clear that while some were novel diagrams or well designed maps, the majority of them seemed like very simple tables and charts. Like this10:

See how the simple categorization above of day labourers allows for the creation of new language (“Archetype 06 - Risk-averse Day Labourer”) and a lens through which future data sets, decisions and problems can be viewed.

But it’s not obvious exactly why these dimensions were chosen on which to categorize day labourers. Why segment them by the length of their world view?

The answer is that categorization is an expert skill.

You need to be able to comprehend an entire system to be able to categorize things effectively11.

A categorization in turn can embed and scale your expertise across an organization.

In cases where the consultant has some domain expertise (not always true) and they’re coming in to help an organization adapt or build new processes the first go-to tool should be a simple categorization. Simple of course, refers to the simplicity of the framework, not of the knowledge and expertise that went into choosing the categorization.

But as an expert you can’t simply force your expertise on the client. Instead you need to build the framework together…

We’ve shown that we want to make our own frameworks, they should be true and they should often be simple categorizations. Now, I want to show you how co-creating them with clients is the ultimate key to allowing them to be socialized, adopted, referenced and ultimately drive change in an organization sometimes for years to come.

This is the IKEA effect - the idea that you’re much more invested in cheap furniture that you built with your own hands than fancy furniture that comes pre-assembled12.

The same is true for frameworks. It’s ok to do the work of sensemaking on your own but it’s better to do it with the client. If you co-create it with the client you get three pleasing effects:

Here’s a real example from some client work last year.

Problem: the client is creating a bunch of content and looking to scale up their content production but their existing performance is very mixed and overall not meeting expectations.

Solution: frameworks to the rescue! (how did you guess I was going to say that?)

After a day or so workshop with the client and the editor in chief we co-created a simple categorization for their content to better help them the user intent for a keyword before they created the content.

The categorization looked something like this:

And this gets embedded and referenced in the master content schedule by assigning every article a grade (A,B,C,D in the second column) or categorization:

This framework helped them write stronger briefs, invest more strongly into areas of competition and also track and monitor performance on a more granular level.

Importantly - note the difference here between a situation where as the consultant you say “you should make better content” and a day-long process of understanding the failure of their existing content process, co-creating a simple categorization, testing that categorization against historical data and then creating the changes in the process doc and working that through with the editor in chief.

Here’s another example of a more visual framework. Also from my own work last year. This one was an accidental success (and really was the genesis for all of my framework thinking since).

A large media company needed to get better at commerce content fast. They needed a better understanding of how it worked and a better plan for executing it.

I put together a strategy deck (30-40 slides maybe) and, in reality the whole thing could be boiled down to “slide 6” which stopped the meeting dead and became the reference object for the whole project. Here it is:

This is simple, but importantly it’s TRUE. Note the 70/30 revenue split? These numbers were based on another property they owned so they had reason to believe it and think it a true framework.

It’s… deceptively simple. And actually pretty hard to do in practice (despite everyone buying into the strategy from top to bottom they ended up completely ignoring the box on the far right. Oh well.)

One thing missing here was a good name - over time it was referenced as “slide 6” (it wasn’t slide 6) or “that diagram you showed”. This is clearly sub-optimal and I think a better name (especially one that emphasized the holistic nature of doing all of this at once) would have helped the framework get executed fully.

Here’s a lovely simple example I’ve referenced many times over the past few years.

Problem: a client needed a way to maintain content quality as they scaled up dramatically. They published long-form product reviews.

After locking ourselves in a room for a day (notice a common theme?) we flipped the concept of defining quality and instead created a minimum threshold for our content to meet:

Does this benchmark seem overly simple to you? Good! Five bullet points that allow you to grade a piece of content to say “this meets our standards or doesn’t” is exactly the simple useful thing we needed.

Later, we translated this into a scoring system - get 4/5 people in a room and have them all rate the same article 1-10 on each of these bullets and you can say “this article is 7/10” and “this is 6.4 / 10”. This descriptive power is turning the abstract framework into a more quantitative model.

And of course, note the co-creation.

With great power comes great responsibility… Who recognizes the following situation: you present a body of work to an executive team and one item - either a throw-away phrase or a single idea “sticks” with an executive and they grab hold of the language and suddenly every meeting they’re in they’re using this one phrase, most of which is entirely out of context or irrelevant.

I’ve definitely been in this situation. It’s painful for two reasons - firstly because your framework had a real use and a real intended meaning and that’s now impossible with the executive bastardization. But also - it causes confusion and frustration with the employees who can often recognize that the framework the exec is forcing on them doesn’t make a lot of sense.

Here’s an example from a few years ago - in the middle of an exec strategy read out I referenced the hub, hero, habit framework:

In truth - this was my fault. I’d had a longer strategy deck I’d prepared that got slimmed down and I’d left in the reference to the framework without the explanation of how it would work in application for that client.

The fallout was that the “hub, hero, habit” framework was referenced by the leadership team in repeated ways but without any real directive, causing confusion for the teams. I don’t think any meaningful action happened as a result[empty].

If you’ve read this far hopefully you’re bought into the idea that frameworks are useful and effective. So… how do you get better at making them?

As I think about the last few years of my own work and I try and understand my own thinking I’ve come to the answer that doodling and diagrams are the way to evolve your thinking.

You can think of it as something like:

Doodles -> Diagrams -> Frameworks -> Models

(Yes, this is a framework!)

Here’s an example - this post:

Was a simple doodle that turned into a mini framework of sorts for thinking through my consulting work and led to the idea of “media design”:

All the projects I’ve seen fail have failed because they have been too focused on one axis of the spectrum and the strategy or execution hasn’t acknowledged the full system - from ignoring the brand implications of the content to not fully understanding the human editors who have to execute a vision.

Media Design is about designing for success by looking at the system and how the parts interplay to make each perform better by bringing them into a shared context.

I’ve been following and collecting interesting visual thinkers for a while and I’ve collected a few of my faves here:

Venkatesh consistently flirts with the boundaries of reality with his doodling, diagramming and thinking. One thing I love about his work is that he’s not afraid to switch between hand-drawn doodles, powerpoint diagrams and flowcharts (or any other medium you can think of).

This one is a particular favorite of mine, quiver doodles:

This recent post the extended internet universe actually has multiple different mediums of visual thinking - drawing, 2x2, constraint triangle.

You didn’t think you were going to get through this post without some cyberfeminism did you? This is out of left field but it’s my hands-down favorite Instagram account right now. Feminism, sex, diagrams, process flows and more. Hard to describe and mildly NSFW but mind-expanding:

Instagram: @nahee.app

Ben Thompson is pretty well known both for his doodles and for his frameworks. Here’s a diagram from his most famous aggregation theory:

If you look at all of their work you can see how convoluted or involved ideas become simpler and simpler over time as they boil them to their essence. Aggregation theory is an excellent example of this from Ben Thompson. (but remember! The goal is to create your own frameworks, not stuff aggregation theory into every strategy deck you make).

By the way these are all archived and will hopefully be maintained over on my wiki: wiki/diagrams and doodles.

A key factor for the success of frameworks is their ability to travel - the ability for a simple framework to be repeated, referenced and leaned on while you’re not in the room.

Giving your framework a strong name is essential to the spread of the concept - and Eugene Wei has an excellent post on this with the appropriately catchy title compress to impress:

“There will come a day when you’ll come up with some brilliant theory or concept and want it to spread and stick. You want to lay claim to that idea. It’s then that you’ll want to set aside some time to state it distinctively, even if you’re not a gifted rhetorician. A memorable turn of phrase need not incorporate sophisticated techniques like parataxis or polysyndeton. Most everyone in tech is familiar with Marc Andreessen’s “software is eating the world” and Stewart Brand’s “information wants to be free.” Often mere novelty is enough to elevate the mundane. You’ve spent all that time cooking your idea, why not spend an extra few moments plating it? It all tastes the same in your mouth but one dish will live on forever in an Instagram humblebrag pic.”

So… do as Eugene says - spend a few minutes plating the framework13.

This is an area that I’m deliberately trying to get better at (note how all of my above examples lacked good naming… ). Naming is not a strong suit of mine but I think studying language, poetry and memes is a good start…

Two good resources for naming things (though both are slightly more focused on naming “brands” I think the concepts are solid):

a 3-step process for naming by Ben Pieratt

Onym - collection of naming resources.

The wonderful article I quoted early in this post from Simon Roberts is going to crop up again here (bolding mine):

Models cause people to “perceive social reality in a way favourable to the social interests of the enchanter” (Gell 1988: 7). I’m sure we’d like to think that our interests are coterminous with those of the people we advise. More often than not I suspect they are. But isn’t it worth remembering the power our models have over those we provide them to and how they exert that power?

Perhaps more importantly it’s worth reflecting on the sometimes restrictive and constraining power that our models might exert over their creators. In pursuit of certainty in the face of uncertainty, is it not sometime the case that the enchanter becomes the enchanted?

As per my older piece the consultant’s grain every time we enter a project we need to understand that we bring our own biases, ideas and ideologies to the table. And frameworks are an excellent way of embedding ideology inside an organization. So tread carefully.

Thanks for sticking with me for this long-ish post. Like I mentioned early on - attempting to force pre-built frameworks into my consulting work has been a major error in the past few years and so I’m still course-correcting and relatively new to building my own. If I could explain this better I’d have written a shorter post…

To recap where we got to:

How are you using frameworks in your work? Leave a comment below, drop me an email ([email protected]) or hit me up on Twitter (@tomcritchlow)! Thanks.

–

Much thanks to all of the folks who reviewed early drafts and left notes and feedback including Luke Stevens, Elan Miller, Brian Dell, Will Critchlow, Nitzan Hermon and more.

If you want to dive down this rabbit hole there’s a lengthy but very approachable piece here: analogy as the core of cognition (PDF). ↩

For more on this rabbit hole there’s a longer conversation around the distinction between a framework and a model in this Twitter thread with myself, Brian and Venkatesh. ↩

I took the liberty of changing these quotes to swap the word ‘model’ for ‘framework’ to fit my definitions and make these quotes flow easier ↩

My brother Will pointed out that the big consulting firms are some of the biggest framework dealers around. He’s right of course - shortcuts and ‘first principles analysis’ are not mutually exclusive ↩

There’s a free 209 page PDF here for those that are interested in learning more about the Jobs to be Done framework: whencoffeeandkalecompete.com ↩

Page 383 of The Field Study Handbook by Jan Chipchase ↩

Remember that by definition every framework is leaky. The trick is to tease apart the right part of the situation to abstract. For more on that read this great piece the law of leaky abstractions by Joel. ↩

Jan weighed in on Twitter with some additional thoughts and notes in this thread. ↩

Studio D put together a report called Paddy to Plate and this is an image from page 107 ↩

Page 133 from Paddy to Plate ↩

It seems there’s a fair amount of academic research that backs this up and I found these great quotes: ‘Experts notice features and meaningful patterns of information that are not noticed by novices.’ and ‘Experts’ knowledge cannot be reduced to sets of isolated facts or propositions but, instead, reflects contexts of applicability: that is, the knowledge is ‘conditionalized’ on a set of circumstances.’ Both of these from How People Learn - Chapter: 2 How Experts Differ from Novices ↩

This is a real thing by the way - look it up: the IKEA effect ↩

In his post Eugene references the idea that every year at Amazon there’s a named ‘theme’. I wonder if naming client engagements is an untapped area of opportunity to frame the work… ↩